| The

end of neo-liberal economics: Great Crash of 2008 and the

demise of the Regan-Thatcherism

October

17, 2008.

The end of neo-liberal

economics: Great Crash of 2008 and the demise of the Regan-Thatcherism

Kumar David

The ‘global-state’

(G7 and some G20 governments, central banks, and the IMF

and IBRD multilateral agencies) intervened in the international

banking system during the October 11-12, 2008 weekend, financially

on an unparallel scale, and politically with resolute, coordinated,

authority. One is left wondering what is left of global

finance capital that is distinctively capitalist anymore.

The implications of intervention on such a scale are momentous

for international banking and finance. If the intrusion

goes much further, British, French, German and other governments

will become the primary owners of banks in a watershed reversal

of Regan-Thatcher neo-liberalism after 30 years. For the

ilk of Francisco Fukuyama, this is the end of his-story.

One more thing,

US global financial hegemony is over, forever, that is for

sure; an economic-multipolar globe based on a new sharing

of global power-positions is taking shape. For years I have

been insisting that Globalisation-II (my copyright!) is

different from the early decades of globalisation. The present

financial crisis will complete the transition. The economic

strength of the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China) nations

in manufacturing, energy and certain technologies, will

be complemented by financial clout. Consider dollar reserves;

China $1.9 trillion, the Petro Middle East $1.3 trillion,

Russia $500 billion, then add Japan, South Korea, Taiwan,

Hong Kong and Singapore; well over $5 trillion in total.

How will these countries use their financial power? They

will become global centres of finance capital, acquiring

banks and finance houses, while American and European finance

capital slips. Economic power will be underpinned by financial

expertise and deep pockets.

The scale of

intervention

There is a sea change in how political business is done

in Washington, London, Paris and Berlin; a paradigm shift

whose significance is sinking in slowly. Ideologically,

it is borne out by the news that the banks were given no

choice; it did not matter whether they wanted government

support or not, the heads of the relevant banks were called

in and told, whether they like it or not, the Treasury was

going to inject liquidity, that is part nationalise them.

US Treasury Secretary

Hank Paulson, announcing the decision on Monday (13) said

that this was “not what we like to do but what we

have to do”. He went on to add that the government

was buying shares in banks because the “alternative

was totally unacceptable”. A frank admission that

free-market capitalism had terminated in a catastrophic

meltdown of the world’s greatest banking system and

it was being part nationalised; make no mistake about the

stark and explicit reality.

Nationalisation

in the UK is voluntary, but its extent is stunning. Britain’s

second largest (Royal Bank of Scotland - RBS) and sixth

largest (HBOS) banks are now under a controlling government

stake - in the case of RBS 60%. A third of all bank branch

outlets in the country will be state controlled. Market

capitalisation of RBS was $76 billion in February this year,

but it has fallen since and a $35 billion investment in

5% preference shares is buying the government 60% ownership.

The numbers for HBOS are still not known and Lloyds, the

UK’s fifth largest bank, is also being part nationalised,

but again numbers are not known. Several smaller banks will

also be affected - Northern Rock and Bradford & Bingley

have already been 100% nationalised. It is evident that

the government is determined to do what it takes to make

the banks liquid, and one need have no doubt that it will

take nationalisation as far as necessary, and even all the

way.

Ben Bernanke,

the US Fed Chairman said on the 13th, “our strategy

will evolve with the crisis; we will not stand down till

we achieve our objective”. The US has so far thrown

only $250 billion of the $700 that Congress approved in

early October, towards bank nationalisation (the Americans

need a euphuism for nationalisation, so they call it “injecting

liquidity”). However, a larger proportion is likely

to be thrown into the nationalisation programme eventually.

It is difficult

to estimate what share of bank ownership will end up in

government hands - Washington is not even willing to name

the nine banks earmarked for immediate medication but eight

are known (Bank of America, CitiGroup, Wells Fargo, JP Morgan

Chase, Goldman Sacks, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, Bank

of New York Mellon, and State Street - phew, reads like

a roll call of the Himalayan heights of banking!) Let me

put the ownership size estimation in perspective. The market

capitalisation of Wachovia was $76 billion in February 2008,

but when it went belly-up in September its banking operations

were acquired by CitiGroup for $2.16 billion; Wachovia shares

which were trading at $38 in January sank to $10 before

the debacle, and were 97 cent junk on acquisition day.

The market capitalisation

of Bank of America and CitiGroup were $200 billion and $140

billion, respectively, in February, but because of enormous

market volatility there is no certainty of how much they

will be valued at today, except to say the numbers will

be much lower. The government’s intention is to buy

10% preference shares to the tune of $25 billion in each;

the share of ownership accruing to government will depend

on valuation on the purchase date. JP Morgan Chase and Wells

Faro will see injections of $20 billion each and Goldman

Sachs and Morgan Stanley $10 billion, BoNY-Mellon and State

Street get much smaller amounts. Half of the earmarked $250

billion will go into these nine big banks; the remainder

will be made available for thousands of smaller banks and

thrift societies that proliferate across the US. It is hard

to imagine that Uncle Sam wishes to be a stake holder in

these midgets; some other arrangement will be worked out.

There is a possibility

that developments may spiral further out of control. For

example, it is estimated that RBS shares continued to dive

even after partial nationalisation and market capitalisation

at close on Black Friday (10 October) was down to $21 billion.

The British government’s share values are said to

have declined by $1 billion and it will face criticism if

its investments continues to depreciate. Hence there will

be temptation to nationalise the bank altogether and take

it off the stock market. The same could happen in other

European countries. Are we on the road to omni nationalisation

as in 1948? Is it going to be a full 180 degree reversal,

a wholesale trouncing of Regan-Thatcher liberalism? Time

and crisis will tell.

It is not possible

within the confines of this article to mention all developments

in Europe, the Far East and Australia-NZ. Let me only mention

that the rest of Europe is pouring $1.8 trillion into bank

recapitalisations, mainly Germany $680 billion and France

$490 billion; the Australian government has turned to full

blown populism; and the Chinese government, at last, is

paying lip service to growing China’s domestic market.

Paradoxically,

this process is not being led by socialists and social-democrats

at all. Gordon Brown hangs out at the extreme rightwing

margin of social democracy and Nicolas Sarkosy came to power

on a centre-right, anti-socialist, platform. To confound

matters most is George Bush, though tensions were stark

at the October 13th press conferences. Paulson and Bernanke

spoke in the language quoted above, but Bush was at pains

to emphasise “these measures are not intended to take

over the free market”. Tension must be mounting within

the ruling cabals in Washington and elsewhere and could

become more acute after November 4th.

The secret to

unlocking these paradoxes is to grasp that the contradictions

of capitalism are driving its political captains to constrain

and sometimes negate their very own system. It would, however,

be wrong to read too much into these incipient developments,

apart from taking some intellectual delight. A regular e-mail

friend, Swaminathan Palendra, put it like this: “That

is very interesting, Kumar. So, in other words, capitalism

is trying to re-adjust to save itself and in that process

may give birth to some unforeseen global changes ( which

will most probably be positive ), but not necessarily change

the basic structure of capitalism”. Rather well put

and to the point I thought.

The preceding

crisis and spread to the real economy

The antecedent events are not unknown but a brief review

is necessary. However to keep it brief I will use a compressed

point form presentation.

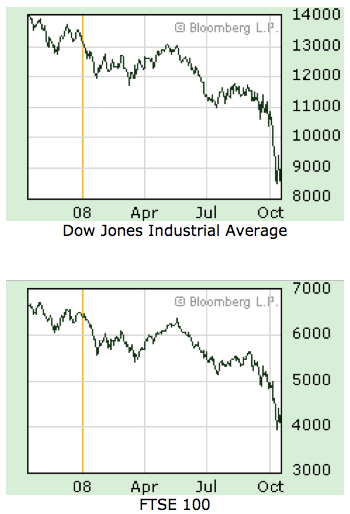

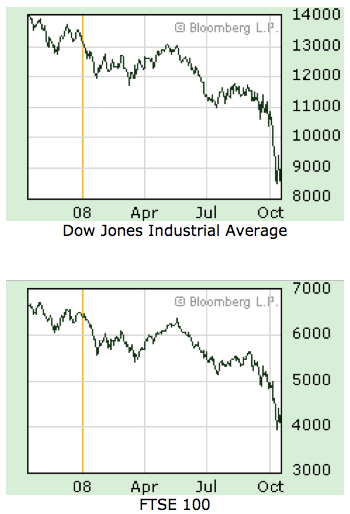

a) The crash was appalling, the worst since the Great Depression

(GD) of 1929-33. Banks whose names are household words,

giant Financial institutions and mammoth Mortgage companies

(collectively, BFMs) are failing in droves. Stock markets,

worldwide, were in turmoil. The almighty Dow was down 39%

in an year; European stock markets were in tumult; Nikkei,

Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korean, Australian and New Zealand

indices were at their lowest in years, in some cases decades;

the Russian stock exchange closed down for days at a time;

the Indian rupee is at a record low. The combined nominal

asset valuation wiped out on global stock markets since

the start of the crisis in mid-2007 was about $15 trillion.

That is, $15 trillion of global capital asset values just

vaporised! (This paragraph is updated to Friday 10 October).

b) American and

EU government reactions were similar. In the worst cases

BFMs go bust (Lehman Brothers) or are nationalised (Fannie

and Freddie in USA, Northern Rock and Bradford & Bingley

in the UK). In other cases central banks extend easy loans

to ease liquidity (examples are too many to name). In still

other cases banks are forced to restructure - sell themselves

to another bank (Wachovia, Washington Mutual), or change

from Investment Banks to ordinary Commercial Banks (Goldman

Sachs, Morgan Stanley), or concede a government purchase

of shareholding. The most ‘pro-capitalist’ option

is when the government takes over bank’s bad debts.

This last approach I will call PP.

c) PP is Paulson’s

Package, the recent $900 billion US scheme. The US Treasury

will buy bad debts and mortgages from banks at a reduced

price after valuation. Once these ‘toxics’ are

removed from balance sheets, banks can breathe more freely,

trust each other, and make inter-bank loans; this is called

re-liquefying banks. It is hoped that thereafter the financial

system will return to normality. The government also hopes

‘toxics’ will recover value and can one day

be sold at a profit. This is the theory; nothing happened

in the first two weeks.

d) On 8-9 October

all the developed economies cut interest rates by between

0.5% and 1%. Nevertheless, finance capital and the ‘analysts’

woke up next morning panting like vultures feeding on a

decaying carcass. “Not enough, not enough, cut interest

rates more and more; pump more, pump more of the workers,

widows and taxpayers savings into the BFMs; save rotting

capitalism” and Stock markets continued their rout.

G7 finance ministers (leaving out Russia) met in crisis

in Washington on October 11, desperate for a coordinated

response to avert a depression. IMF Head, Dominique Strauss-Kahn,

told a G20 meeting “the financial system is on the

brink of a global meltdown”.

e) At first it

appeared that the crisis was mainly in the financial sector,

not yet spreading to the real economy, the productive sector:

manufacturing, agriculture, and real services - not financial

or war related services. Hence, output and employment were

holding their heads above water, initially. However the

signs of spreading to the real economy emerged. US consumer

demand began declining steeply; Japan’s machinery

output fell for the last three months; in September it was

down 14.5% compared to last year. America’s emblems,

General Motors and Ford, started wobbling. US unemployment

rose to over 6% and looked like 10% was on the horizon.

Prices of cereals, commodities, oil, metals started falling

steeply on fears of a deepening recession and declining

demand. There is even talk of global deflation. Crisis has

percolated into the real economy and a recession in the

real economy is already upon the West. Erosion in export

oriented sectors in the rest of the world has commenced.

Prospects for decoupled-depression

I have in recent months been saying that Asia and Latin

America can avoid a deep recession (they cannot avoid dislocation

and fall in growth rates, stock-markets have already been

hammered) if they take correct policy decisions. This option

still remains open because the economy - employment and

output - is steady; banks remain solvent; and growth, though

lower, remains strong. But the problem is that though Latin

America has taken some necessary policy decisions, Asia,

including China, so far, has not. What are the policy decisions?

Countries like China and India need to place emphasis on

domestic consumption not exports (creating internal demand

and wealth), regional economic cooperation, and regional

banking and financial restructuring.

One thing is

certain, US global financial hegemony is over, forever;

that is for sure. An economic-multipolar globe based on

a new sharing of global power-positions is emerging. For

years I have been insisting that Globalisation-II (my copyright!)

is different from the previous phase, Globalisation-I. This

financial crisis will complete the transition. The economic

strength of the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China) nations

in manufacturing, energy and certain technologies, will

be complemented by financial clout. Consider dollar reserves;

China $1.8 trillion, the Petro Middle East $1.3 trillion,

Russia $500 billion, then add Japan, South Korea, Taiwan,

Hong Kong and Singapore; over $5 trillion in total is my

estimate. How will these countries use their financial power?

They will become global centres of finance capital, acquiring

banks and finance houses, while American and European finance

capital slips. Economic power will be underpinned by financial

power.

Two factors are

decisive; the impact of the turmoil itself, and the internal

class struggle - Latin America shows the importance of the

internal class struggle and political leadership. Trotsky’s

remark that the principal crisis in the world is the crisis

in the leadership of the working class remains true today;

but amend “working class” to read “less

privileged and middle classes” to reflect current

social and economic reality in both developed and developing

countries.

Analysis

‘Analysts’ (apologists for capitalism) in Bloomberg,

Financial Times, the Economist, Wall Street Journal and

such magazines, websites and TV channels, say the crumble

will worsen. Their chorus: “It’s going to get

worse before it gets better”. For sure, it is not

possible to predict how deep the crisis in the real economy

will go; there is an old saying that you can never predict

a recession or how deep it will be, you can only look back

and analyse it. The half truth here is that psychological

factors are at work, in addition to economic trends and

data.

There are two

fundamentally different approaches to understanding the

global rout of the capitalist financial system; the bourgeois-apologetic

(BA, though it could just as well be named BS) and the Marxist.

Within the BA school, which dominates Western media, academia

and websites, there are many variants, such as those who

blame market greed, those who blame former Fed Chairman

Alan Greenspan, or Bush tax policies, or bad regulatory

practices. But all BAs have one thing is common: “There

is nothing inherent and endemic in the capitalist system

that leads to catastrophes; it’s just that somebody

did something wrong”, that is their swansong. It’s

not methane that is depleting the ozone layer; it’s

the fault of some bilious cow that farted!

Agreed antecedents

The apologists and Marxists both agree on empirical antecedents

of the systemic collapse. A huge amount of unjustified credit

has been created; unjustified because it should have been

clear that a vast number of recipients of credit would not

be able to meet their repayment obligations. This refers

not only to sup-prime house mortgages (poor quality borrowers)

and credit-card consumers (even people without incomes),

but even big financial fund managers, speculative investors

and businesses. Secondly it is also agreed that banks and

finance companies wanted to share the risk. To spread risk

around they created many innovative financial devices, collectively

called derivatives, and sold them throughout the financial

system. This is similar to insurance companies reinsuring

a multitude of risky deals with all other such companies.

The thorny problem

is that derivatives were packaged together and sold in parcels

to other banks and financial companies, who repackaged them

again with still other risk contracts and resold in more

bits and pieces, here and there and everywhere. The result

is that nobody knows how much bad credit is lurking, where

it is hidden, or who will crash next. Peter S Goodman (New

York Times, 8 October) says that the derivatives market

has grown to $531 trillion which is much too large to believe

but even half of this would be colossal. The reason why

banks are refusing to ease up liquidity and lend to each

other is that no one knows which bank will go down next.

Another way in

which fictitious capital was bloated-up were asset bubbles;

that is, the value of stock market holdings and houses kept

rising during the last 10 years in an utterly irrational

manner. The underlying company was making no improvements

or expansion, the houses and neighbourhoods were not being

refurbished, but values rose and rose and rose; a bubble,

a fake, and it had to burst. Bill Lussinhide in his personal

website estimates that, at peak, the valuation of shares

in the US stock market was an “atmospheric and unprecedented

185% of total GDP”; its historical average value should

only be 58% of GDP.

The immediate

psychological cause of the crash was panic; banks realised

that their debts would not be serviced, lenders saw that

debtors were empty vessels, mortgage providers went broke

when house owners defaulted as sub-primes ended their ‘easy

period’, asset values on stock markets plunged and

collateral of all forms (shares, houses and pieces of paper

on which derivative contracts were written) turned into

rubbish. A huge crisis of confidence set in and so was born

the Great Crash of 2008. These are the agreed facts, the

empirical antecedents, agreed by BAs and Marxists alike.

Schools of apologists

There are many sub-schools but two basic versions of BA

prevail - the free marketers and the regulators, overlapping

neo-liberals (Austrian School economists) and pinkish Democrats

(theory-less empiricists). The former say the mistake was

interfering with the natural boom and recession cycle; they

say monetary and fiscal intervention stalling the 2001 recession

only bottled things up and made the later explosion worse.

They are like my grandmother: “Don’t take those

bloody antibiotics, let the body go through its natural

processes and cure itself, in the end it will be stronger”.

Greenspan’s low interest rates, Bush’s tax refunds

to middle classes to stimulate spending, fiscal revenues

(big government) and big spending (except defence), are

their culprits.

The pinks point

to failures of disclosure, inadequate regulatory frameworks,

lax oversight and 15 years of low interest rates stimulating

excess credit. Failure to enact legislation to monitor hundreds

of derivatives was courting disaster. Legions of pink academics

have been warning that derivatives had become an alphabet

soup of products whose tentacles had spread dangerously.

Warren Buffett

observed, five years ago, that derivatives were “financial

weapons of mass destruction, carrying dangers that, while

now latent, are potentially lethal” and financial

wizard George Soros said he refused to touch them “because

we don’t really understand how they work.”

The Congressionally

unchallenged “Oracle” Greenspan refused to regulate

derivatives; he rebuffed even minimalist proposals, he trusted

the market to spread, smoothen and regulate risk. “What

we have found over the years in the marketplace is that

derivatives have been an extraordinarily useful vehicle

to transfer risk from those who shouldn’t be taking

it to those who are willing to and are capable of doing

so,” he told the Senate in 2003 (many of these quotes

are from the NY Times article). He believed that derivatives

spread risk and allowed financial services to take more

complex risks on a grander scale than they might otherwise

have done. He told Congress that “there is nothing

involved in federal regulation per se which makes it superior

to market regulation”. But today market infatuated

liberals get laryngitis when asked to explain the egg in

the face of unregulated free-markets.

Crisis theory

Every economics textbook has a chapter or two on conformist

Business Cycle theory. There is some natural overlap since

the roots of conventional wisdom lie in Marx’s thesis

of periodic crisis built into the capitalist system. What

is distinctive about the textbook versions is that it lacks

historical sweep. The scope is limited to discussions of

whether monetary or fiscal policy blunders reinforced a

plunge, recounting of leading and lagging indicators, or

a historiography of past recessions. Bourgeois economics

is short on theory and lacks an analysis of longer, secular

movements and accumulations of fundamentals that lead to

systemic shocks. What conventional economics is good at,

especially after Keynes, is policy prescriptions on how

to delay or mitigate a recession, or climb out of a depression

- a one of experience.

Marx developed

a rather more far-reaching compendium of ideas. As capital

expands through a boom, profits rise. Then a natural process

linked to capitals expansion, market competition, the challenge

of sustaining higher productivity, established wage levels

and constraints in labour availability relative to capital’s

growth, combine to diminish the rate of profit. This is

endemic, inherent and natural to capitalism. Clever methods

were devised to maintain unsustainable profits - financial

engineering, working on endless credit expansion. New profits

came not from production, not from the real economy, but

from thin air. Gigantic bubbles of puffed up credit (fictitious

capital) allowed fake money to make money out of fake money.

This con worked for more than a decade, but then the fundamentals

won and the hoax collapsed. Both schools of apologists say

that if Bush did this, or if Greenspan did that, or if financial

regulations were thus restructured, all would have been

well. Rubbish!

“The notion

that Greenspan could have generated a totally different

outcome is naïve,” says Robert Hall a Stanford

economist. If credit explosion and derivatives driven financial

engineering were stalled, the fall in the rate of profit

would have arrived sooner. The intrinsic business cycle

of capitalism will have its say like a river flowing to

the sea, you can dam it and divert it, but you cannot stop

it. Let’s give the final say to old Greenspan himself;

in his new book he says: “Governments and central

banks could not have altered the course of the boom”

- QED.

Below, four one-year

stock market charts at close on 15 October, 2008

Article from: http://www.groundviews.org/

|